WASHINGTON — It's only mid-July, but it has already been a long, hot summer for a lot of people in the U.S., particularly in the West. The devastating heat wave along the Pacific Coast has been a major news story for the last few weeks.

Look closer at 2021 and you'll find that extreme weather events have been a dominant theme. And as the costs in dollars and lives stack up, it's getting harder for Washington and the world to ignore what look like the growing impacts of climate change.

Last week, Tropical Storm Elsa made its way up the Eastern Seaboard with torrential rains and gale-force winds.

The storm started in the Caribbean and moved to the Gulf side of Florida before it crossed over the state and quickly moved up the coast, affecting Georgia and the Carolinas, even places as far north as Boston. On the way, it spawned tornadoes around Jacksonville, Florida.

Elsa arrived in the first half of July, the earliest the World Meteorological Organization (the body that names storms) has had its fifth named storm in the Atlantic. Elsa was preceded by Ana, Bill, Claudette and Danny.

We'll know in the coming weeks whether that means an especially active hurricane season, but regardless, an early start to the destructive season is never a good thing.

Meanwhile, there was the intense heat wave on the West Coast, which hit Oregon, Washington and British Columbia. Late June brought especially high and dangerous temperatures to places not used to them, leaving scores of people dead.

The record temperatures in the Pacific Northwest — 108 in Seattle, 116 in Portland and 117 in Salem, Oregon — would be scorchers anywhere, but they hit the area especially hard because they were so uncommon.

Many households in that part of the country lack air conditioning, including about a fifth of the housing units in Portland, according to census data. And that led to deaths.

According to the state medical examiner, more than 100 people died in Oregon during the last heat wave. Thirty more died in Washington state. And late last week, forecasters said another heat wave was making its way to the West Coast.

The high temperatures In Death Valley are forecast to be 120 degrees or higher through Wednesday, and on Sunday the forecast high is 132, according to AccuWeather. All that heat could leave very dry land when wildfire season begins.

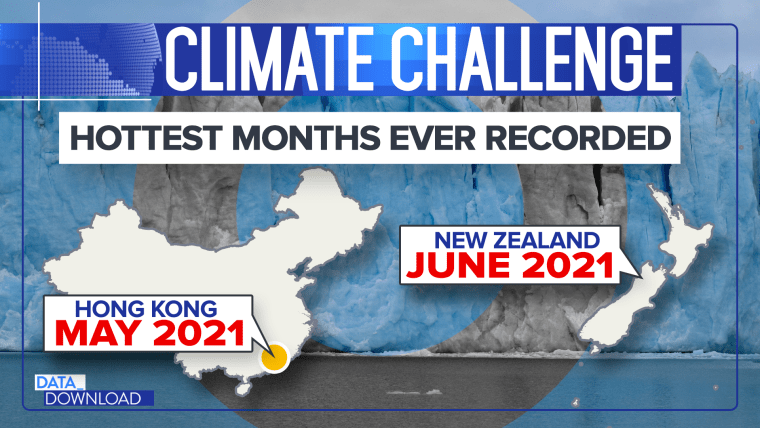

The U.S. has been hit especially hard in the last few weeks, but it isn't alone in its climate challenges. Around the globe, temperature anomalies have been a big part of the year. Hong Kong had its hottest May ever this year, while New Zealand, where it is now winter, had its hottest June.

And they may sound like a distant memory, but remember the winter storms that enveloped the Southern U.S. and caused massive damage in Texas back in February? There is evidence that storms like those may become more common with climate change.

Instability in the jet stream may mean cold temperatures dip south more frequently. And this winter's storm showed some of the costs if that trend holds.

The event became the most costly winter storm in U.S. history (some estimates put the damage at north of $155 billion) in large part because of the chaos it caused to Texas' infrastructure.

Some people were left without power for days when the state's electrical grid failed. That, coupled with the low temperatures (some in the teens), meant people died from hypothermia and others suffered carbon monoxide poisoning as they tried to stay warm with cars and space heaters. At least 150 people died in the event.

And beyond the electrical grid, many of the state's water systems weren't adequately insulated, and they froze. Pipes burst. Potable water was scarce and had to be shipped in.

The takeaway from Texas and from many of this year's other weather events is that the country may not be prepared for what the climate has in store for it. If such extreme storms and events continue, power grids, water systems and construction standards may have to be upgraded or retrofitted. That equals a lot of money.

Washington has been debating whether climate change is real or dangerous for years, but events like those may move the conversation from the esoteric to the pragmatic. Debating science and future impacts is one thing. Dealing with real-life, real-time losses of life and of money is another.